Abstract

Background

Epidemiological data show that myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are associated with increased risk of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD). However, knowledge about the retinal findings in these patients is lacking. This study was conducted to examine retinal ageing and the prevalence of a hallmark of AMD; drusen, in patients with MPNs. Further, we examine the role of chronic systemic inflammation, considered central in both AMD and MPNs.

Methods

In this single-centre cross-sectional study, we consecutively enrolled 200 patients with MPNs. The study was divided into three substudies. Firstly, we obtained colour fundus photographs from all patients to evaluate and compare the prevalence of drusen with the published estimates from three large population-based studies. Secondly, to evaluate age-related changes in the various retinal layers, optical coherence tomography images were obtained from 150 of the patients and compared to a healthy control group, from a previous study. Thirdly, venous blood was sampled from 63 patients to determine the JAK2V617F allele burden and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), a marker of systemic inflammation, in MPN patients with and without drusen.

Findings

Patients with MPNs had an increased risk of having large drusen compared to the three population-based studies OR 5·7 (95%CI, 4·1–8·0), OR 6·0 (95%CI, 4·2–8·4) and OR 7·0 (95%CI, 5·0–9·7). Also, we found that the retinal site of drusen accumulation – the Bruch’s-membrane-retinal-pigment-epithelium-complex was thicker compared to healthy controls, 0·43μm (95%CI 0·17–0·71, p = 0·0014), but there was no sign of accelerated retinal ageing in terms of thinning of the neuroretina. Further, we found that MPN patients with drusen had a higher level of systemic inflammation than MPN patients with no drusen (p = 0·0383).

Interpretation

Patients with MPNs suffer from accelerated accumulation of subretinal drusen and therefore AMD from an earlier age than healthy individuals. We find that the retinal changes are located only between the neuroretina and the choroidal bloodstream. Further, we find that the drusen accumulation is associated with a higher JAK2V617F allele burden and a higher NLR, suggesting that low-grade chronic inflammation is a part of the pathogenesis of drusen formation and AMD.

Funding

Fight for Sight, Denmark and Region Zealand’s research promotion fund.

1. Introduction

,

,

]. Recently it has been shown that patients with MPNs are at increased risk of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [

], a progressive degenerative disease of the retina, causing loss of central vision. Worldwide AMD accounts for 8.7% of legal blindness, and it is the most common cause of visual impairment in the western world [

]. The hallmark sign of AMD is drusen. Drusen consist of cellular debris located between the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Bruch’s membrane. AMD-associated lesions: drusen and pigmentary abnormalities, characterise the early stages of AMD. In addition, the late stages of AMD have either characteristic neovascular lesions or sharply demarcated areas of retinal atrophy, defined as neovascular AMD and geographic atrophy (GA), respectively [

]. Despite extensive research, the exact pathophysiology of AMD remains unknown. Certain risk factors are known such as age, cigarette smoking and genetic susceptibility [

,

]. In recent years evidence have emerged demonstrating the role of the immune system, including inflammation, in the pathogenesis of the disease [

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, ]. Since MPNs cause massive inflammation and a recent register study has reported that patients with MPNs have a significantly higher risk of neovascular AMD [

], it is intriguing to investigate these patients in the context of AMD.

]. Further, we assessed the JAK2V617F allele burden as a marker of inflammation, since the JAK2V617F mutation is seen as a key driver of MPN-associated chronic inflammation [

].

2. Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

]. Patients at the Department of Haematology, Zealand University Hospital (ZUH), were invited to participate in the study. Patients were consecutively enrolled for substudy one until we reached 200, and inclusion was conducted between January 2017 and October 2019. Of the 200 patients, 150 were enrolled in substudy two to match the number in the healthy control group. Finally, 63 of the patients not receiving immunomodulating treatment were enrolled in substudy three.

,

,

].

]. This control group did not have fundus photographs taken and could not be used as controls for substudy one.

In substudy three NLR and the key driver of MPN-associated chronic inflammation JAK2V617F mutation was compared between MPN patients with drusen and those without.

2.2 Imaging and grading method

] (supplementary material 1.1). This allows comparisons to several studies, including the population-based studies used in this study. We chose to compare our results to populations of European ancestry since ethnicity differences have been reported [

].

] using drusen size and presence of pigmentary abnormalities to classify AMD (supplementary material 1.3).

One investigator (CL) graded all images, and another investigator (MKN) re-graded 80 images to test intergrader agreement.

] (supplementary material 1.1).

For substudy two, we obtained optical coherence tomography images (SD-OCT, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) from 150 of the patients. The images were examined in Heidelberg Eye Explorer version 1.9.10.0. We used the automated segmentation and the thickness profile part of the software to measure the thickness of the different retinal layers, and segmentations was checked manually (supplementary material 1.2).

].

2.3 Blood sampling

For substudy three, venous blood from antecubital veins was sampled from 63 patients, not receiving immunomodulating treatment – 35 of the patients had drusen, and 28 had normal ageing changes. The blood was sampled in an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid-coated (EDTA) tube and analysed on Sysmex KX-21NTM (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan), to measure white blood cells count; lymphocytes count, and percentage; neutrophils count, and percentage; and monocytes–basophils–eosinophils mixed count and percentage. Sample volume for the count was 50 µl. NLR was calculated by dividing the absolute neutrophil count by the absolute lymphocyte count. The JAK2V617F mutation analysis was performed on peripheral blood EDTA anticoagulated blood with highly sensitive real-time quantitative PCR on an ABI Prism7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), on fluorescence-activated cell sorted (FACS) monocytes, lymphocytes and granulocytes on a FACSVantage (BD Biosciences). DNA was extracted using a MagnaPure robot (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.4 Outcomes

The main outcomes were drusen size (largest present), pigmentary abnormalities, early-, intermediate- and late AMD, neuroretinal- and RPE-BM thickness, NLR and JAK2V617F allele burden. Secondary outcomes were area-covered-by drusen; drusen count, and drusen type.

2.5 Statistical analysis

].

We analysed the data using the SAS statistical software package (SAS ver. 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.).

]. We found strong agreement for drusen size (weighted kappa=0·87) and drusen count (weighted kappa=0·86), moderate agreement for drusen area (weighted kappa=0·79) and weak agreement for pigment abnormalities (weighted kappa=0·47).

In substudy two and three, linear regression models with age as exposure variable were used to investigate the relationship between the continuous outcome variables; layer thicknesses of the retina, NLR and JAK2V617F allele burden. Non-normal data were transformed. Where outcome was independent of age, a two-sided t-test was used for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for non-normal data. Otherwise, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to estimate differences between the two regression lines corresponding to groups.

2.6 Role of the funding source

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding author confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

3.1 Study population

For substudy one, 200 patients were enrolled. One was excluded post hoc since the diagnosis of MPN was later questioned. Eight patients were excluded due to poor image quality of the obtained fundus photographs. As a result, 191 patients had gradable photographs and were included for analyses.

]

For substudy three, we collected blood samples from 63 of the patients.

Table 1Characteristics of the participants in substudy 1, 2 and 3.

PV: Polycythaemia vera, ET: Essential thrombocythemia, PreMF: Pre-myelofibrosis, PMF: primary myelofibrosis JAK2V617F: mutation in the JAK2 gene, CALR: calreticulin gene, MPL: MPL gene, gene encoding the thrombopoietin receptor.

3.2 Substudy 1 – AMD-associated lesions and AMD-stages

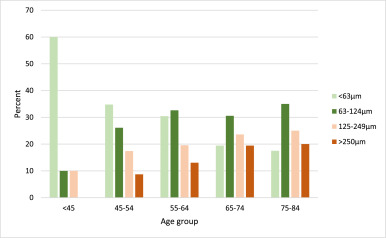

Fig. 1Age-specific distribution of maximum drusen size within a radius of 3000 µm from the fovea of the worst eye in patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms.

Drusen count: Only 6·4% of patients with MPNs had no drusen in the macular area, 34·2% had between one to nine drusen, and 59·4% had ten or more drusen. The number of drusen increased with increasing age. Ten or more drusen were seen in 20·0% of patients younger than 45 years and 71·8% of the patients aged 75–84 years.

Drusen type: For patients with drusen larger than 63 μm (129 patients), the drusen-type were primarily soft drusen (91·1%). In 11 patients, both soft drusen and one of the two types, cuticular drusen or subretinal drusenoid deposits, were also found.

Drusen area: The area-covered-by drusen within the grading-grid was greater than 0·069 mm2 in 49·7% of the patients, greater than 0·146 mm2 for 26·5%, greater than 0·487 mm2 for 12·4%, greater than 1·27 mm2 for 4·9% and greater than 2·5 mm2 for 2·2% of the patients.

Pigmentary abnormalities: Of the 184 patients without late AMD, we found pigmentary abnormalities in 25 cases (13·6%; CI 9·4−19·3%). Nine had increased pigment, nine had hypopigmentation, and seven had combined types. Accordingly, 16 patients (8·7%) had increased pigment, and 16 patients (8·7%) had decreased pigment. None of the patients younger than 45 years had pigmentary abnormalities. For the age groups 45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and 75–84 years, the prevalence was 13·6%, 4·3%, 17·1% and 22·2%, respectively. Except for the age group 55–64 years, pigment abnormalities were increasing with age.

Table 2Age-specific prevalence of all stages of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) in patients with MPNs and the prevalence rates of late AMD in the same age groups from The Beaver Dam Eye Study, The Blue Mountains Eye Study and the Rotterdam Eye Study.

MPN: myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The age groups in The Beaver Dam Eye Study and The Blue Mountains Eye study are different from the age groups in this study: 1age group 43–54 years. 2age group 75–86 years. 3age group 49–54 years. 4The Rotterdam Study did not include patients younger than 55 years.

Since the classification of the earlier stages of AMD is different in our study compared to the population-based studies, it is not possible to compare these stages.

3.3 Results compared to prevalence rates from population studies

Fig. 2Comparison of the prevalence of drusen >125 μm as the largest drusen present within a 3000 μm radius of the fovea between patients with Myeloproliferative neoplasms and three large population-based studies (Beaver Dam Eye Study, Blue Mountains Eye Study and Rotterdam Study).

Table 3Age-specific odds ratios for large drusen >125 µm within a 3000 µm radius of the fovea for MPN patients compared to the Beaver Dam Eye Study, The Blue Mountains Eye Study and The Rotterdam Study.

Only RS gives the exact prevalence of drusen size 63–125 µm; 35·7%, 43·2%, 41·0% in the age groups 55–64 years, 65–74 years and 75–84 years, respectively. The comparable prevalence in MPN patients was 32·6%, 31·4% and 38·9%. There was no significant difference between MPN patients and the RS population in intermediate-sized drusen (P = 0.11).

Drusen area: The area-covered-by drusen within the grading-grid was greater than 0·069 mm2 in 49·7% of the patients and greater than 1·27 mm2 for 4·9% of the patients. These areas correspond to approximately to 0·3% and 4·5% of the macula area. In BMES similar numbers are given. Drusen covered more than 0·2% in 15·3% of the participants and more than 4·7% in 6·2% of the participants.

Pigmentary abnormalities: To compare with BDES and BMES, we excluded the age group younger than 45 years and patients with late AMD. Twenty-five (14·4%) of the MPN patients had hyperpigmentation, hypopigmentation or both. In the BDES and BMES, the prevalence of any pigmentary abnormality was 13·1% and 11·9% (data was not available to exclude patients aged 85+ in the BDES). There were no significant differences between the prevalence of any pigmentary abnormalities in patients with MPNs and the BDES (OR 1·1, CI 0·7–1·7) or the BMES (1·2, CI 0·8–1·9).

Excluding further the age-group 45–54 years to compare with the RS population, the prevalence of any pigmentary abnormalities in patients with MPNs was 14·5%. The prevalence in the RS study was 7·0% (age group 85+ excluded). Patients with MPNs had a significantly higher risk of pigmentary abnormalities compared to the RS population (OR 2·2, CI 1·4–3·5).

In patients with MPNs, 8·7% had hyperpigmentation, and 8·7% had hypopigmentation. These numbers for hyper- and hypopigmentation was for BDES 12·2% and 8·3%, BMES 12·1% and 5·8%, RS 5·9% and 4·4%.

Patients with MPNs had a significantly higher risk of having hypopigmentation compared to the BMES (OR 1·8, CI 1·0–3·0) and a significantly higher risk of both hyper- and hypopigmentation compared to the RS population (OR 1·8, CI 1·1–3·1) (OR 2·0, CI 1·1–3·6).

3.4 Substudy 2 – retinal thickness

The thicknesses of the retinal layers were approximately normally distributed. The RPE-BM layer was 0·43μm (ANCOVA, 95%CI 0·17–0·71, p = 0·0014) thicker in patients with MPNs compared to the healthy control group. Mean RPE-BM thickness in the macula for patients with MPNs was 14·39μm (95%CI 14·19–14·58) compared to 13·96μm (95%CI 13·75–14·16) for the healthy control group (which was older than the MPN patients, p-value <0·0001)

There was no significant difference in neuroretinal macular thickness between patients with MPNs and the healthy control group (ANCOVA, p-value=0·2990). Mean neuroretinal macular thickness in patients with MPNs was 286·55 μm (95%CI 283·85–289·25) compared to 288·95μm (95%CI 286·54–291·36) for the healthy controls.

We also evaluated each sublayer of the neuroretina in the centre-, inner and outer subfield independently (supplementary material 2).

3.5 Substudy 3 – chronic systemic inflammation and drusen formation

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio was not normally distributed and log-transformed. Linear regression lines were fitted for each group and showed that NLR was not dependent on age. We found that MPN patients with drusen had a significantly higher NLR than MPN patients without drusen, estimated difference 1·37 (T-test, 95%CI 1·02–1·86, p = 0·0383).

The JAK2V617F allele burden was non-normally distributed and did not fit an approximately normal distribution with transformation. Linear regression showed that the allele burden was not dependent on age. We found a higher allele burden of JAK2V617F among patients with MPNs and drusen (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P = 0·0754). Thirty-three out of 35 patients (94·3%) with MPNs and drusen had the JAK2V617F mutation, and the median allele burden was 33·00 [IQR 11·00–56·00]. Only 24 out of 28 of the patients (85·7%) without drusen had the JAK2V617F mutation, and the median allele burden was 17·50 [IQR 5·55–28·50].

4. Discussion

], showing that MPN patients are at increased risk of having neovascular AMD. Further, we find that MPNs are not only related to neovascularization but also to the subretinal accumulation and the formation of drusen. We found no difference in the neuroretina suggesting that the retinal changes are not due to overall accelerated ageing of the retina, but rather to the accumulation of debris between the neuroretina and the choroidal bloodstream.

,

]. Patients with MPNs have large drusen in their macular area, and a higher prevalence of late AMD compared to population studies. In our study, we found a higher occurrence of GA than neovascular AMD. The register study by Bak et al. reports an increased risk of neovascular AMD, but our results indicate that GA could be even more prevalent.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

] and chronic inflammation and immune deregulation are common features between AMD and MPNs [

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

]. Thus, chronic inflammation has been proposed as both a trigger and a driver of clonal evolution in MPNs [

]. The neoplastic clone is a major source of inflammatory cytokines, released into the systemic circulation, and contributing to the symptom burden in patients with MPNs, and the inflammation-mediated comorbidities, including cerebral- and cardiovascular diseases, the increased risk of autoimmune diseases and second cancer [

,

]. Similar to MPNs, AMD has been associated with systemic diseases characterised by immune modulation or inflammation, such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease and AIDS [

,

,

Pennington KL, Deangelis MM. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. doi:10.1186/s40662-016-0063-5.

,

]. Rozing et al. have proposed a two-level hypothesis of the development of age-related degenerative diseases, including AMD []. The hypothesis includes two steps: the first step is an accumulation of retinal damage due to ageing, and the second step is the following inflammatory host response to these damages. Both steps should be present to develop AMD. In patients with MPNs, inflammation plays a pivotal role in disease pathogenesis and therefore possesses a massive “second step” contribution to the development of AMD. NLR is a good and relatively stable indicator of subclinical systemic inflammation [

], and we found that MPN patients with drusen have a significantly higher NLR and a tendency of higher JAK2-allele burden than MPN patients without drusen, further supporting a role for chronic inflammation in drusen formation and the pathogenesis of AMD.

,

] comparative molecular, genomic and immunological studies between drusen/AMD and MPNs are envisaged to unravel novel insights into disease-promoting mechanisms and how to modify disease evolution by targeting the common denominator for disease evolution and progression – chronic inflammation.

]. In donor eyes of patients with late AMD, the same mononuclear cells have been found to accumulate [

].

,

]. The components of drusen have been shown to retain microglia in the subretinal space and thereby sustain the inflammatory response which turns destructive and can influence photoreceptor and RPE integrity [

].

].

]. The result of this could be that only patients with mild MPN disease reach old age. Consequently, this could lead to an underrepresentation of older patients with severe disease and accordingly, a lower estimation of late AMD in these age groups.

,

,

]. Since cardiovascular diseases are common in MPNs patients they are often being treated with statins. Many of the patients in our study also receive immunomodulating treatment, and this may prevent some of the patients with intermediate AMD and GA from turning in to neovascular AMD, a possible explanation of the high occurrence of GA in our study.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that patients with MPNs have a significantly higher prevalence of drusen and consequently AMD from a younger age than persons without MPNs. Further, the MPN patients with drusen have a higher level of chronic systemic inflammation compared to patients without drusen. These findings add evidence to the concept that chronic systemic inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of AMD. However, additional studies – including the very early stages of MPN development – are needed to elucidate the underlying causal association between AMD and MPNs and the factors eliciting drusen/AMD in patients with MPNs. Studying patients with MPNs have the potential to reveal novel aspects on the pathogenesis of AMD.

Acknowledgements

The first author would like to thank “Fight for Sight, Denmark” and Region Zealand for funding her PhD.

Further, we thank Grace Hambelton, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, United States for assistance in OCT image evaluation.

Funding

Fight for Sight, Denmark and Region Zealand’s research promotion fund.